Amanda Tobin and Levi Prombaum, members of the CARE SYLLABUS team, interviewed guest-curator Wendy Red Star about the different valences of care that inform her artistic practice.

October 2020. This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Image: Detail from Wendy Red Star, Baaitchi (Good Things), 2020, from Bíiluuke (Our Side) series

Levi Prombaum: I want to learn more about how care is important to you as a creator. My first question is about your research, in relation to histories of forced movement of Indigenous objects, which may end up far away from their homes, families, and communities. Could you say more about your encounters with Crow objects as you research? About what it means to both choose an object, but also, to have an object choose you?

Wendy Red Star : Any time I have the opportunity to go to a museum that has Crow objects, there is this overwhelming feeling of excitement. I'm just dying to see the object, to totally nerd out. I can hardly contain myself! And I don't think the collection manager or the curators quite understand the sort of desperate need to see these objects. It's one of my most favorite things to do in the world.

When I finally get to see the objects, it's just a feeling of pure joy. Then, after I settle down a little bit, I am looking at all the details. Maybe things that people might not initially be attracted to, like the knots or maybe the unfinished parts. Those small details start me thinking about the person who created it. I think that's kind of what draws me in are those aesthetic decisions that I'm starting to pick up that are more subtle, like in a piece of beadwork. I might notice a tiny little color shift where it's just a few shades lighter and a peak color that is just such an incredibly smart decision. That gives me an insight into the mind of whoever made that, and then that makes me want to know more.

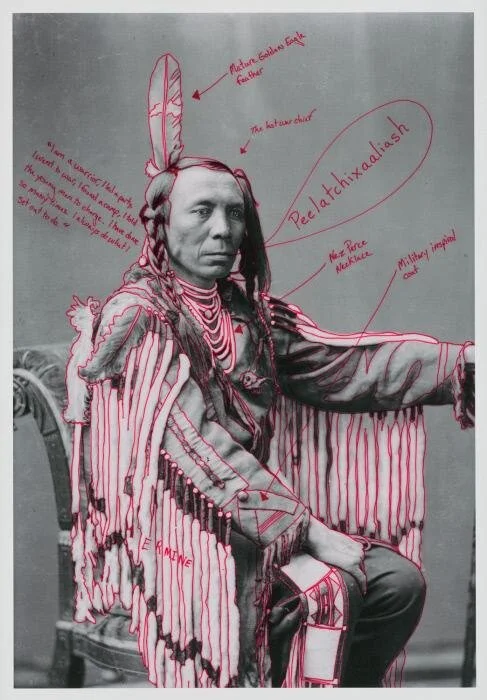

Wendy Red Star, Peelatchixaaliash / Old Crow (Raven), 2014, from the the series 1880 Crow Peace Delegation.

And then sometimes there are these objects that are completely plain and I don't think they would be special at all. It actually makes me think of one of the chiefs that's in the MASS MoCA Kidspace Exhibition - a man named Old Crow. There was this very plain bag, but next to it was an interesting red ring that had these feathers on it. Tiny little feathers like flicker feathers. The bag itself wasn't very pretty, or anything striking. When I looked at the accession card with the information in it, I learned that it was Old Crow, and to actually hold something that is Old Crow’s was quite cool. It was a medicine charm for picking berries. So you're supposed to put the feather charm in the bag and bring it for the berry picking season and you'll get the best berries. This is one of my favorite objects now.

There's something to having those objects, and also having that description. And I think about that when I'm writing about the delegation photos. It’s a really interesting photo, but to actually give you a little insight into, for instance, the fact that Medicine Crow was a judge -- one of the first Crow Indian judges -- just adds a certain dynamic to that image that wasn't there before. That makes it even more intriguing.

So I’m either really awestruck by an object and then it gives me clues to the decisions of how that object was made that I find really intriguing. Or it could be: ‘What is up with this object? Why is this interesting? Why this, out of everything, when you've got something just dripping with color and pattern?’

LP: Those different situations strike me as similar in the sense that there is a piece of information that's not immediately evident, which is made so either from your close observation or from something circulating around the object that sparks something for you.

WRS: Absolutely. And for Native people who have their ancestral objects in collections, to actually have a neighbor who that object belongs to. When that happens, that's so exciting to me, because even if there's not a photo, there might be a census record or something that might give me a little more information, and animate that object in a new way.

Amanda Tobin: What drew you to visual arts as a career path? Why use visual art to share your research into your Apsáalooke heritage?

“Art has been the way for me to speak the loudest. It’s my clearest form of communication.”

WRS: Art articulated all these things that I was learning that I couldn’t do in a conventional way. I can create this visual research and output. I would love to be a history teacher, I always wanted to. But I also wanted to have some room to experiment and not to be so rigid. And I feel like art really offers that freedom to me. Art has been the way for me to speak the loudest. It's my clearest form of communication.

I had terrible self-esteem when I was little. I thought I was stupid, and I was told that I wasn't smart. I worked really hard -- I think part of that was my dyslexia. I've never learned in a conventional way at all. And being held back made me feel like I didn't fit or wasn't successful.

To tell you the truth, I had no idea what I was going to do. But I had parents who were like, ‘You're going to college.’ So when I went, I was like, ‘What am I going to do? I can't do English, or math or sciences. But I guess I can try art. But art isn't going to make me money, what a horrible fate.’ I feel so sorry. I still talk to art students today who say ‘I'm never going to make any money.’ Which is not true. I started out as a graphic designer, because I thought that's how you can make some money.

Because of graphic design, I took foundation art classes, and the one that totally clicked was because I had this great professor. She told me, ‘I think you need to switch to sculpture.’ That was a terrifying call to my mother, but she was very supportive and said, ‘I'm just happy that you're getting an education.’ That's how things make sense to me, is through sculpture, I felt like sculpture was also the thing where you could get away with the most.

AT: Could you describe the process of how you create an annotated portrait? What's the research process like? Where do you do your research? How does the process of creating feel?

WRS: I am constantly, constantly looking. It usually starts with a Google search or something like that, typing in historic images of Crow people. In regards to the 1880 Crow Delegation series, it started out with two images of Chief Medicine Crow. And then from there, I asked myself the question, well, what happened on the day that he sat down to take that photo? It was taken in Washington, D.C., in 1880, by Charles Milton Bell. Once I started looking at Bell, I found more photos that were taken not just of Medicine Crow, but of other chiefs that had the same photo session and went on the same trip. From there, the question is: who's this chief? And some of them I recognized from just growing up on the reservation, and some of the chiefs I did not recognize. I didn't know who Two Belly was. I didn't know who Long Horse was.

I found out about the census, and how important it is for researching the history of Native people. I'm very thankful for that. I hear the census come up politically now, and if I had not done the research that I'm doing, I would think, what's the big deal with the census? But doing the research, it's so important to have these census records that give you a tiny bit of information, especially when Native people at that time didn’t really have birth certificates to document their lives.

I also learn new information just by finding a chief's name. I did a Google search on Pretty Eagle, and that's how I would find, for instance, that his remains were stolen when he passed away, and the tribe was able to get them back. So it's kind of like a rollercoaster. Things keep evolving, and I become more and more curious.

LP: Julia Bryan Wilson wrote some incredible analyses of your work in the recent issue of Aperture, ‘Native America,’ that you guest-edited. She used the phrase “merging of forms” to describe your Family Portrait series, in reference to repeated photographs within the star quilt pattern. This got me thinking about a related, but opposite tendency around authorship in your work, where different artistic voices often remain rather distinct from one another. Could you say more about the process of welcoming in other images and imagers in your work?

Wendy Red Star, Two Prom Dates, 2011,

from Family Portraits series

WRS: When we were talking about some of the work that I made recently, where I was using multiple photos of the same person, and then was asked, ‘is there an aesthetic, decorative element to that?’, I love getting these questions because I just made that work and I haven't had the opportunity to really sit down and understand what it was that I'm doing. When I make work, what’s fascinating is to me is that I'm working with a part of my brain that knows exactly what it wants to say, what it's doing. But when I'm finished with the work, I don't quite understand it until, sometimes, years later. And then it all makes sense. It's like an unconscious part of my brain that I'm tapping into. I’m thinking about the multiples, and about kinship and genealogy and these multiple selves. You know, I'm part of my great- great-grandma, my great-great-grandfather, my dad, my daughter. We’re all parts or copies of those people or traits that are embedded in us. Thinking about all those ancestors just lined up behind you is fascinating to me.

I’m really interested in connecting with these makers, and they are often not alike. So for me it’s important when I'm working with a historical photo not to discount who the photographer was and what their agenda was, because that is really important to tell a story of that individual and how those individuals came together or how that meeting came together. And sometimes that aspect is really important, and this needs to be brought forth in a piece.

And sometimes, this is not so much the case, because it’s so deeply embedded in the work. For instance, I'll use my father's slides, and that seems more intertwined with my own intimate story and my own agenda. It might not be quite as visible, but I always feel like I'm working intergenerationally regardless. In everything that I do, there’s an intergenerational aspect of collaboration that I’m attuned to. I feel like I’m a chain in all of these stories that I'm trying to connect together. It just depends what I decide to kind of push forward, or what doesn't have to be as loud within a specific piece.

Detail from Wendy Red Star, Baaitchi (Good Things), 2020, from Bíiluuke (Our Side) series

LP: I wanted to ask you more about the hand in your work, about how it can operate as a metaphor of care: like in the Bíiluuke (Our Side) series, where your hand is photographed engaging Crow objects, or in the Crow Delegation series, where, as a viewer, I imagine your hand in the process of outlining or annotating the original photographs. Could you say more about seeing, touching, and holding - and what seeing might have to with our hands?

WRS: You know, my background is in sculpture, so my way of understanding is achieved through using my hands and building something. When I got to UCLA, they had all the graduate students in one warehouse. It was really cool, but it was all the different media. So there was no genre. There was photography, there was painting, and there were the interdisciplinary students who were considered super weird because they had offices and everybody else had studio space. It was a real treat to get to walk around the hallways and peer into people's studios and see how they work. At that point, I was really still trying to silo myself to an idea of what sculpture is. But I was so attracted to all the photography majors and what they were doing.

There's this one artist named Brenna Youngblood. I really loved her practice, and their approaches were so different. Some photo students were really precious about their photos, where there was different lighting, where they produced the photos in the art building versus using the lighting at the studio. They would print different color proofs for the lighting, they’d have three color proofs, and they would wear white gloves when they touched the prints.

But Brenna, you go into her studio and she had spilled soda and empty bags of chips and she'd be eating while also cutting her photographs. She would touch her photos with her hands and you'd see her fingerprint, and then she'd place glue on the back of it and just stick it up on something. I loved this. There's something so amazing about just kind of tearing into these photos. And yet the work that she made was so powerful and it retained a certain respect even though her actual practice was very messy. It really influenced me to see that she could be so physical and tactile with this medium. You had somebody in that same department who was vacuuming and painting their walls white and using gloves and doing multiple color prints. So to me, this was really intriguing.

As far as my hand is concerned, I feel like that's what I need when I look at photos. I love photos and a good photo I can just stare at all the time. But I think my form of investigating is to get to know more, to force myself to really go beyond that. And so sometimes that means writing directly on the photos or sometimes that means cutting them -- that's another way to really run into things that I hadn't noticed when I was just looking at it within the whole context and background. Sometimes, it means I'll make a necklace that somebody is wearing in the photograph, and then I actually physically have that object out of the photo that I'm interacting with. It's a way to get into the reality of that photo in the most intimate or tactile way that I can.

AT: What’s meaningful for you about archival research?

WRS: I'm really interested in historical archives that contain Crow materials, like the National Museum of the American Indian or historical societies related to a specific town. The archives that exist have the cultural material of my community. They're really important and controversial at the same time. There’s this tension that's happening with these materials that are away from their source. Sometimes, those materials were taken in violent ways or arrived there out of a practice of survival.

“Multiple archives, located all over, might have the missing puzzle piece, and my parallel archive brings them together and says ‘Here, here's this little bit of the timeline that's been missing that I would like to share.’”

I also keep a parallel or addendum archive. My archive involves putting or piecing things together in a way that fills in the gaps that are missing. And it's like a giant puzzle for me because it's never one archive that has everything. These multiple archives, located all over, might have the missing puzzle piece, and my parallel archive brings them together and says ‘Here, here's this little bit of the timeline that's been missing that I would like to share.’ I don't know if that's the definition of an archive, but that's my definition.

LP: The historian in me wants to ask you more about the historical puzzle pieces that you find. I’ve had experiences doing research in archives where the pieces I find are incredibly interesting, but they don’t seem to be pieces to the same puzzle, and it doesn’t feel like they will ever fit together. What do you do when you have these bits of information that are rich and extraordinary, but don't necessarily make a bigger picture in and of themselves?

WRS: You know, I think this work and this process of looking at information is a slow burn for me, because what ends up happening is I might have that really rich information for ten years and then find another part of that puzzle and be like, ‘Oh, my God, that’s what this is about.’

At the Smithsonian Artist’s Research Fellowship in 2018, I went to the National Museum of American Indian, the National Anthropological Archives and National Museum of Natural History. I just needed to see everything, to become this sponge and absorb everything.

And finally, in a way, certain things come together. Sometimes it can be really frustrating because something might click to me or I might become sort of interested in this specific subject, then don't realize I had a lot of that information for five or seven years already buried in my computer somewhere. So I think those pieces of information that you mentioned will stay relevant, will probably click in somewhere. It will reveal itself in due time. It's just about having the patience for that to happen.

LP: I’d like to briefly touch upon some guiding inquiries of the CARE SYLLABUS. From your perspective, whose role is it to care for whom? And how has the pandemic changed the way you think about care?

WRS: I think there needs to be more caring. And it's interesting in this political time to see who is caring and who's not caring.

This idea of care and the pandemic has been helpful in my life, because before the pandemic I was moving at all times and constantly traveling. And if I think about care for myself, before the pandemic, I wasn't caring and was moving forward at a pace that was toxic. I hear so many artists talking about this as a moment to hit the refresh button in a way, even though it's a completely scary time with so many unknowns. I’ve had this time to sit and work through some things that I was choosing to avoid or unable to attend to.

This time has led to re-evaluating the overextending of myself that I did, which was driven by fear. It felt that the world was so fast-paced. Other artists were in three different places within the same week. It just didn’t seem natural. When the pandemic happened, things were canceled or postponed. I didn’t travel except to see my own family. It’s been a process of realizing that you actually have to care for yourself, otherwise, it’s not going to work anymore.