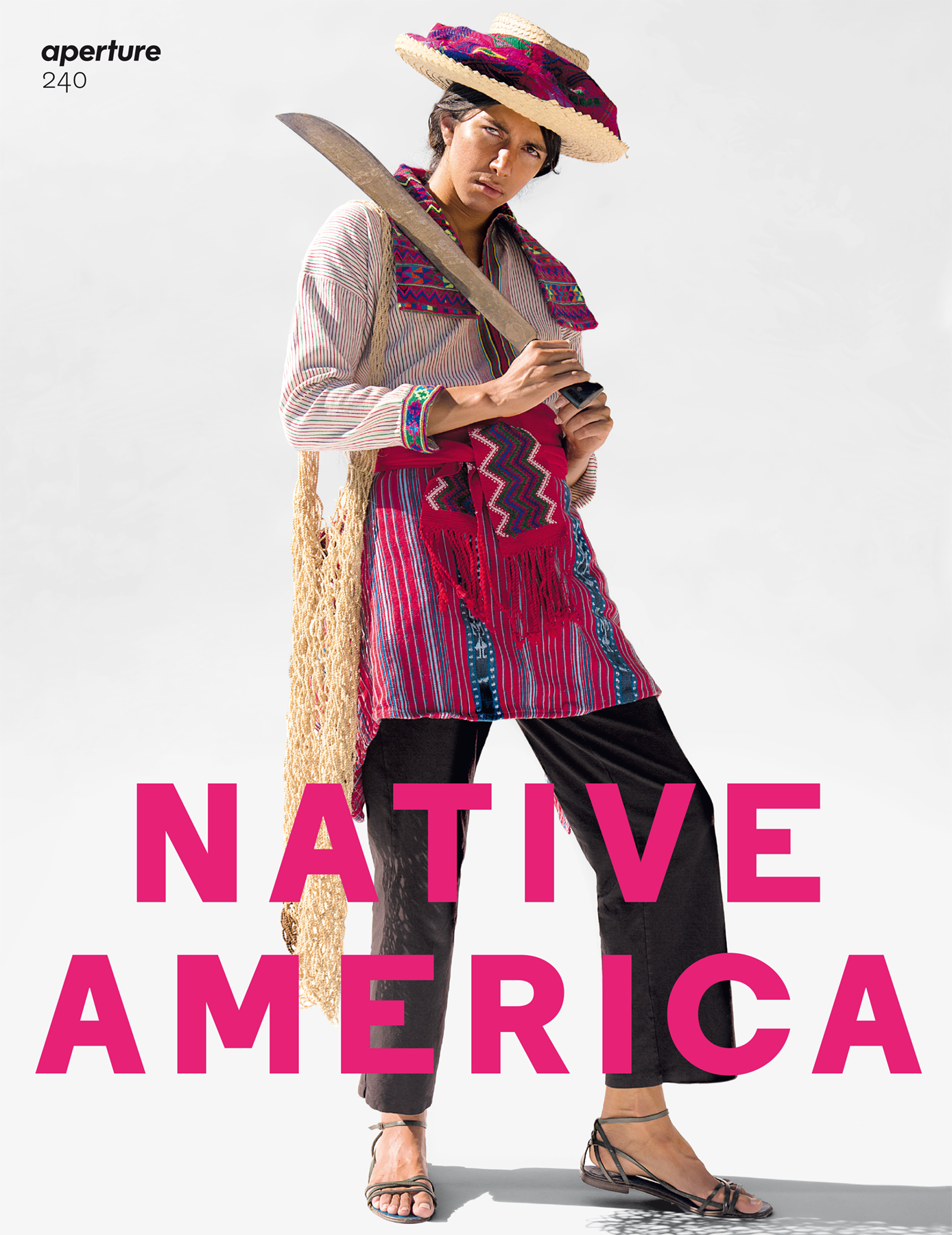

Wendy Red Star recently served as guest-editor for “Native America,” the Fall 2020 special issue of Aperture magazine. As part of this pathbreaking collection of artistic and scholarly perspectives on Native photographers, Red Star interviewed Emily Moazami, Assistant Head Archivist at the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI), about the museum’s roles as a steward of images of Indigenous people and cultures. Two excerpts from this interview are reproduced below. For more information, and to purchase the full issue, check out Aperture’s website.

September 2020. © 2020 Aperture Foundation, Inc., reproduced with permission from the Publisher. This material may not be reproduced in any form without written permission from Aperture.

Wendy Red Star: Making the artwork that I make, using historical images, I’ve seen on social media the popularity of historical images of Native people. A lot of them come from Pinterest. What are the effects of sharing these images, and does this influence the work that you’re doing in the archives?

Emily Moazami: I’m torn, because I can imagine, let’s say, there is a Native teenager who happens to stumble across some of these photographs, and they really inspire them, and maybe they didn’t know these photographs existed of their tribe. So in that way, I think it could be really wonderful. I’m assuming a lot of teenagers are not sitting around searching our collections online, so maybe that’s a way to get them interested. But I get frustrated that people don’t always link back to the original source.

WRS: During my fellowship, I discovered several members of my family who had material objects in NMAI’s collection. It was incredible to also find images of these ancestors in the photography archives. In my excitement in this discovery, I asked if you could help me find as many of the photographers from around the turn of the century who photographed my community in Montana, and, a few months later, you sent me a spreadsheet with fifty-eight photographers.

EM: I went through our catalog records to see what photographers we had who were photographing in the region. I also looked at other institutions’ catalog records -- for example, the National Anthropological Archives -- to find photographs that were taken in the region of the Apsáalooke peoples. There are also some great resources, like biographical dictionaries, those list photographers by state. I looked in the section from Montana, and I saw which photographers were listed as having photographed in the region.

Fred E. Miller, Her Dreams Are True, Apsáalooke Reservation, Montana, ca. 1898-1910. (Also known as Julia Bad Boy-Bear Ground, she was Wendy Red Star’s great-great-grandmother.) Courtesy the National Museum of the American Indian.

WRS: When you were showing me photographs that Fred E. Miller took in the early 1990s, one of the images happened to be of my great-great-grandmother Her Dreams Are True, or I’ve also seen her name written as Dreams The Truth -- her English name is Julia Bad Boy, which is an excellent name. I was thrilled because it’s such a beautiful photograph. She’s sitting in front of this striped background -- you can tell it’s a weaving of some sort -- that really sets off her paisley-style underdress. We found another photograph, of two Crow men with the same background, noting that it was taken at the Bureau of Indian Affairs building, in Crow Agency, Montana. That gave me the location of where my great-great-grandmother’s photograph was taken.

After I finished my research at NMAI, I had a printout of that image of Her Dreams Are True. I decided I should look into another photographer named Richard Throssel, who was also photographing my community around the same time, to see if he took a picture of my great-great-grandmother. I researched his archive, and I found a portrait of her. I was so excited. It looks like she’s a few years older in the Throssel photograph. It somehow felt spiritual to find her.

EM: That’s incredible to have that connection.

WRS: What sort of responsibilities, besides the care of these archives, should institutions have to the contemporary communities these historical records are tied to? What are someways you see institutions building connections with Native communities?

EM: We definitely have a responsibility to Native communities, and we need to take Native voices into consideration when we’re working with their historical records. For example, at NMAI, we respect the wishes of communities in regard to photographs or materials that are deemed culturally sensitive. We would never place culturally sensitive materials online, and if somebody contacts us and wants to publish a sensitive image, we tell them they need to get permission from the tribe.

We have paid internships for Native students who are interested in becoming museum or archival professionals. We’ve had projects where interns have incorporated their Indigenous language into finding aids and catalog records.

At the museum, we see ourselves as stewards of the collection. We’re not owners. And we see ourselves as caring for the collections for future generations. We have a Community Loans Program, where we work in partnership with source communities to send materials back to tribal cultural centers for long-term loans. Recently, one hundred Tewa Pueblo vessels were returned home for display at Poeh Cultural Center in Pojoaque, New Mexico. It was the result of several years of collaboration between the Tewa communities and NMAI. We also practice traditional care, where we incorporate the source community’s wishes for how objects should be cared for, such as if it should be oriented facing a certain cardinal direction. We give opportunities for people to leave offerings. We also have indoor and outdoor ceremonial spaces, where visiting community members can actually use objects to perform a ceremony or blessing on-site -- a lot of museums don’t even let you touch objects.

WRS: The history of NMAI hasn’t always been one of stewardship. When did that switch happen, from the old colonial standard to the stewardship approach?

EM: It’s an interesting question. I believe the museum really started to incorporate Native perspectives and voices into its exhibitions, catalog records, and public programming in the 1970s. I work with a lot of photographs that document the museum’s activities, and I find photographs from that time period documenting curators working directly with Native communities at the museum.

WRS: One of the most fun parts of finding images and objects from my community is that I have wonderful phone calls with my father. I’ll ask him all sorts of questions based on things I saw in the archives or names that popped up. But always in these conversations my dad will end up saying, “Ah, I wish your grandmother or grandpa was still here, because they’d be able to identify these people.” For me that just adds urgency to these conversations, even to talking to my dad about the knowledge he holds. I want to make sure to have these conversations with him, to try to get as much information from him as possible.

“What’s changed is that museum professionals admit that we’re not the experts. People from the source communities are the experts, and the people whose ancestors are depicted in the photographs are the experts.”

EM: In the past, museums have always acted as an authority, and it’s reflected in our catalog records. What’s changed is that museum professionals admit that we’re not the experts. People from the source communities are the experts, and the people whose ancestors are depicted in the photographs are the experts.

Even when you and I were working together, I could help you identify photographic processes, but you were telling me in great detail about all the activities depicted in the photographs. You provided so much personal insight. That is a big change -- this collaborative effort, this dialogue between museum professionals and Native community members.